Posts Tagged statistics

Big data puts an end to the reign of statistics

Posted by mark in Basic stats & math on March 3, 2016

Michael S. Malone of the Wall Street Journal proclaimed last month* that

One of the most extraordinary features of big data is that it signals the end of the reign of statistics. For 400 years, we’ve been forced to sample complex systems and extrapolate. Now, with big data, it is possible to measure everything…

Based on what I’ve gathered (admittedly only a small and probably unrepresentative sample), I think this is very unlikely. Nonetheless, if I were a statistician, I would reposition myself as a “Big Data Scientist”.

*”The Big-Data Future Has Arrived”, 2/22/16.

A Data Sherlock’s best friend: IBM’s Watson

According to this report last week by eWeek, more than 1 million users have registered for IBM’s Watson Analytics service since it launched a little over 1 year ago. Evidently this artificially intelligent (AI) statistician-in-a-box will enable “citizen data scientists” to decipher patterns in the massive pile of information that now flow in from all quarters. Current clients featuring by eWeek range from multinational law firm using it to identify new areas of practice to a UK a care provider looking for factors that improve worker safety. IBM itself now operates an enterprise called Watson Health that deciphers medical imagery, and they bought the digital assets of the Weather Company to help businesses defend themselves against Mother Nature.*

Unfortunately for one of the early adopters of Watson—the MD Anderson Cancer Center at University of Texas (UT)—AI’s current IQ still falls far short of initial hopes.

“On Jeopardy! [Where Watson made its name 5 years ago by defeating the human champions] there’s a right answer to the question [actually the right question for the answer], but, in the medical world, there are often just informed decisions.”

— Lynda Chin, chief innovation officer for health affairs, UT

So it seems that, for the moment, at least, human statistical Sherlocks will not be replaced by AI’s overseen by amateurs at sleuthing out the culprits for cancer or other highly prized information. However, Watson might be as capable an assistant as ‘his’ literary namesake.

*1/6/16 Financial Times “Big Read” on “Artificial Intelligence”, p 5 sidebar.

Sine illusion makes peaks and valleys on graphs look overly variable

An article in the latest Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics (JCGS, Vol 24, Num 4, Dec 2015, p1170)) alerted me to a fascinating misperception called the “sine illusion” that causes misinterpretation of trends in variability. See it nicely illustrated here by vision researcher Micheal Bach. The JGCS, Susan VanderPlas and Heike Hofmann, detail “Signs of Sine Illusion—Why We Need to Care” and provide methods to counteract its misleading effects.

If you see a scatter plot that goes up and down with seemingly large scatter at the bends, get out a ruler to get the true perspective. That is my take home message for those like me who like to be accurate in their assessments of data.

“The illusion is explained in terms of a perceptual compromise between the vertical extent and the greater overall dimensions of the section at the turn of the sine-wave figure.”

– RH Day and EJ Stecher, “Sine of an illusion,” Perception, 20; 1991, 49–55.

How you can make statistics persuasive for your political cause

For a very unsettling demonstration of statistics being easily biased to whatever result you like, go to this blog by science journalist Christie Aschwanden and chart maker Richie King. Scroll down to the Hack Your Way To Scientific Glory control panel. There you can play your hunches as to how Democrats versus Republicans affect the U.S. economy. With a few changes in how you define the factors and measure the response, the results can be manipulated as you like. Print out the final statistics and use them to beat up your political opponents. What fun!

Fisher-Yates shuffle for music streaming is perfectly random—too much so for some

Posted by mark in Basic stats & math, Consumer behavior on July 28, 2015

The headline “When random is too random” caught my eye when the April issue of Significance, published by The Royal Statistical Society, circulated by me the other day. It really makes no statistical sense, but the music-streaming service Spotify abandoned the truly random Fisher-Yates shuffle. The problem with randomization is that it naturally produces repeats in tracks two or even three days in a row and occasionally back-to-back. Although this happened purely by chance, Spotify consumers complained.

Along similar lines, I have been aggravated by screen savers that randomly show family photos. It really seems that some get repeated too often even though it’s only by chance. For a detailing of how Spotify’s software engineer Lukáš Poláček tweaked the Fisher-Yates shuffle to stretch songs out more evenly see this blog post.

“I think Fisher-Yates shuffle is one of the most beautiful random algorithms and it’s amazing that such a complicated problem can be solved in 3 lines of code in some programming languages. And this is accomplished using the optimal number of operations and optimal amount of randomness.”

– Lukáš Poláček (who nevertheless, due to fickleness of music listeners, tweaked the algorithm to introduce a degree of unrandomization so it would reduce natural clustering)

Believe it or not–sweet statistics prove that you can lose weight by eating chocolate

A very happy lady munching on a huge candy bar caught my eye in The Times of India on Friday, May 25. Not the lady—the chocolate.

A very happy lady munching on a huge candy bar caught my eye in The Times of India on Friday, May 25. Not the lady—the chocolate.

After tasting a variety of delectable darks from a chocolatier in Belgium many years ago, I became hooked. However, I never imagined this addiction would provide a side benefit of weight loss. It turns out that a clinical trial set up by journalist John Bohannon and two colleagues came up with this finding and showed it to be statistically significant. This made headlines worldwide.

Unfortunately, at least so far as I’m concerned, the whole study was a hoax based on deliberate application of junk science done to expose phony claims made by the diet industry.

It turns out to be very easy to generate false positive results that favor a dietary supplement. Simply measure a large number of things on a small group of people. Something surely will emerge that out of this context tests significantly significant. What this will be, whether a reduction in blood pressure, or loss in weight, etc., is completely random.

Read the whole amazing story here.

My thinking is while Bohannan’s study did not prove that eating chocolate leads to weight loss, the subjects did in fact shed pounds faster than the controls. That is good enough for me. Any other studies showing just the opposite results have become irrelevant now—I will pay no attention to them.

Now, having returned from my travel to India, I am going back to dip into my horde of dark chocolate.

Null hypothesis significance testing procedure (NHTSP) psyched out

My colleague Brooks Henderson alerted me to this new policy by the editors of the Basic and Applied Psychology (BASP) journal to ban the NHSTP. According to the editorial in their Feb 2015 issue, authors must remove all p-values and the like and not refer to “significant” differences. They also banned confidence intervals, which really makes this new policy onerous, in my opinion.

I do see the sense of focusing on effect sizes and allowing the readers, presumably subject matter experts, to judge their importance. However, although they do “encourage the the use of larger sample sizes”, it makes no sense, I feel, to disregard the impact of small studies on the uncertainty of the results.

Blaming the misuse of NHTSP and p-values in particular for bad science is like letting a bad guy go by saying the gun is at fault.

Picking on P in these times of measles

Posted by mark in science, Uncategorized on February 3, 2015

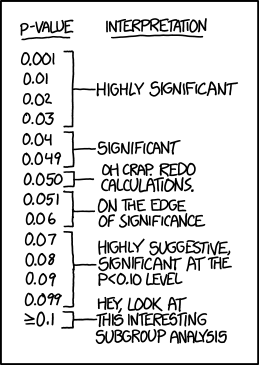

Randall Munroe takes a poke at over-valuers of p in this XKCD cartoon

Nature weighed in with their shots against scientists who misuse P values in this February 2014 article by statistics professor Regina Nuzzo. She bemoans the data dredgers who come up with attention-getting counterintuitive results using the widely-accepted 0.05 P filter on long-shot hypotheses. A prime example is the finding by three University of Virginia finding that moderates literally perceived the shades of gray more accurately than extremists on the left and right (P=0.01). As they admirably admitted in this follow up report on Restructuring Incentives and Practices to Promote Truth Over Publishability, this controversial effect evaporated upon replication. This chart on probable cause reveals that these significance chasers produce results with a false-positive rate of near 90%!

Nuzzo lays out a number of proposals to put a damper on overly-confident reports on purported scientific studies. I like the preregistered replication standard developed by Andrew Gelman of Columbia University, which he noted in this article on The Statistical Crisis in Science in the November-December issue of American Scientist. This leaves scientists free to pursue potential breakthroughs at early stages when data remain sketchy, while subjecting them to rigorous standards further on—prior to publication.

“The irony is that when UK statistician Ronald Fisher introduced the P value in the 1920s, he did not mean it to be a definitive test. He intended it simply as an informal way to judge whether evidence was significant in the old-fashioned sense: worthy of a second look.”

Laws of nature lead to rare events that really ought not surprise anyone

Posted by mark in Consumer behavior on October 18, 2014

Years ago I traveled to Sweden intending to dig up some Anderson family roots. Although I had little luck tracing back the tree (too many sons of Anders!) it was great fun touring this Scandinavian country that seemed so much like home in Minnesota. One thing they had that we did not was a complete wooden warship—the Vasa —which sank on her maiden voyage due to some engineering issues (since then the Swedes have rebuilt their reputation!). After a dramatic movie-reenactment of this ship’s history, the lights came up and I discovered a dear friend of our family sitting right behind me. Unbeknownst to me they’d also gone for a holiday in Sweden, decided to go to the same museum, etc. Miraculous!

It turns out that from a strictly statistical view, coincidences like this really are not so unexpected. As physicist Freeman Dyson put it, “the paradoxical feature of the laws of probability is that they make unlikely events happen unexpectedly often.” A Cambridge mathematician laid this out in his eponymous Littlewood’s Law of Miracles, which states that in the course of any normal person’s life, miracles happen at a rate of roughly one per month. Dyson provided a simple proof of this law as follows. “During the time that we are awake and actively engaged in living our lives, roughly for eight hours each day, we see and hear things happening at a rate of about one per second. So the total number of events that happen to us is about thirty thousand per day, or about a million per month…The chance of a miracle is about one per million events. Therefore we should expect about one miracle to happen, on the average, every month.”*

I wrote all this about Dyson and Littlewood over ten years ago in my May 2004 DOE FAQ Alert ezine. What reminded me of it was this Science magazine review of a new book titled “The Improbability Principle, Why Coincidences, Miracles and Rare Events Happen Every Day” by Professor David Hand, former Chair in Statistics at Imperial College, London. It lays out these five laws that explain why seemingly rare events are really not that unusual.

None of this surprises me. In regards to the time I ran into a friend from Minnesota in Sweden, such encounters must be common that with so many of our inhabitants being of Scandinavian descent, most all of whom vacation in the summer, and go to the same popular attractions. How many of you have unexpectedly met someone you know while traveling far from home? I’d venture to say it’s the majority. That’s what these statisticians are trying to tell us. They really know how to take the excitement out of life. 😉

Odd statistics from the United Kingdom

I’m enjoying a weekend in London prior to a conference in Cambridge next week. I was happy to see in the news that the Prime Minister David Cameron is under investigation by the UK Statistics Authority for biasing figures on in his party’s favor. Evidently the British are more vigilant than the USA on out-and-out self-promoting misstatements.

On a more frivolous note, here are some stats on people in these parts that I found in this recent news on the weird by UK’s tabloid the Express gleaned from the soon-to-be-published book Numberland by Mitchell Symons–a principal writer of early editions of Trivial Pursuit and author of That Book of Perfectly Useless Information, The Book of More Perfectly Useless Information, and Where Do Nudists Keep Their Hankies?:

- A girl reportedly called Thelma Ursula Beatrice Eleanor (spelling TUBE) was born in 1924 on a Bakerloo line train at Elephant and Castle. (I took the Bakerloo line today while bopping around London.)

- The average British adult moves home every seven years. (That seems a bit inconvenient for the parents.)

- One of ten British adults admit to wearing the same item of underwear three days in a row. (I thought it smelled somewhat musty while jammed into the steamy-hot Bakerloo.)

- In 1705 John Smith was hanged for burglary at the Tyburn Tree. After he had been hanging for 15 minutes, a reprieve arrived and he was cut down. Amazingly, he was revived and managed to recover. As a result, he became known as John ‘Half-Hanged” Smith. (This just chokes me up.)